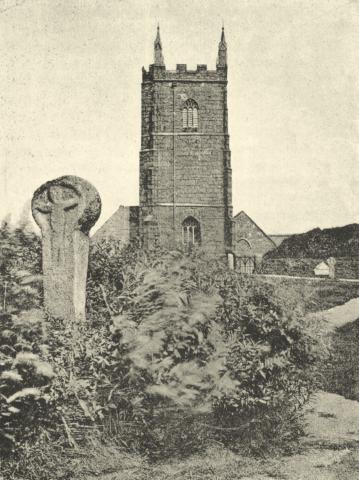

LELANT CROSS.

on the Introduction of Christianity to the Saint Ives District.

As West Cornwall was the earliest seat of civilization in Britain, so it was one of the first parts of the island to embrace Christianity. East Cornwall was evangelised by Welsh missionaries; West Cornwall is indebted to Ireland for its first knowledge of the Faith. Hence it is that nearly all the parish churches of the Land’s End district are dedicated to Irish saints. The churches of Lelant and Saint Ives bear the names of two members of a large company of missionaries who, in the middle of the fifth century, came from Ireland to West Cornwall, and nearly all suffered martyrdom in this neighbourhood. The only remaining records of their history are certain fragments of unknown authorship, and passages in the chronicle of William of Worcester. A manuscript Legendary formerly existed, containing the Acts of Saint Ia (patroness of Saint Ives), which was read in the parish church on her feast day; but it disappeared at the Reformation.

The ancient authorities do not entirely agree as to some of the details in the history of the first missionary expedition to West Cornwall, but they are unanimous in their enumeration of the principal personages who composed it.

One of the converts of Saint Patrick in Ireland was a certain Fingar, sone of a king named Clito. This Fingar, much against the will of his people, renounced his succession to the kingdom, in order to devote himself to preaching the Gospel. With this object he sailed from Ireland, accompanied by a large number of other zealous Christians, among whom were these:

Saint Piala, sister of Saint Fingar, or Finbar.

Saint Ercius, Ertius, or ‘Herygh,’ as William of Worcester calls him. The church and parish of Saint Erth perpetuate his memory in Cornwall. The same authority says of him that he was brother to Saint Elwinus, that he was a bishop, and that he is buried ‘in a certain church situated under the cross of the church of Saint Paul in London.’

Saint Elwin, who according to this chronicler, ‘lies in the parish church of Saint Elwinus near the town of Lelant on the northern sea, about three miles from Saint Michael’s Mount.’ He is now commemorated in the full title of the same parish, which is Saint Uny Lelant.1

Saint Germochus or Germoe.

Saint Breaca, after whom the parish of Breage is named. An unaccountable Cornish tradition asserts that Germo was a king, and Breaga a midwife:

‘Germo

matern,

Breaga lavethes.’

William or Worcester says that Breaca was born in Ireland, and was a nun in the monastery of Saint Brigit.

Saint Maruanus or Mervyn, monk; also called Mirin and Merran.

Saint Levinus or Levan, bishop.

Saint Sinninus or Sennen, abbot, who was at Rome with Saint Patrick.

Saint Crewenna, patroness of Crowan parish.

Saint Buriana, virgin, of Saint Burian parish.

Saint Ia, virgin martyr, patroness of the town and parish of Saint Ives. There seems to be a tradition that she was sister to Saint Ewinus and Saint Ertius. (Lysons’ ‘Cornwall.’)

The church of Gwinear derives its name from Saint Fingar, or Finguar. (Note that Cymric Gw=Gaelic F.)

William of Worcester, who wrote as a traveling antiquary in the year 1478, had picked up a few traditions of these Cornish saints from ‘Thomas Pepderelle of Tavistock, notary public.’ Colgan, an irish priest, whose ‘Hyberniæ Sanctorum Acta’ was published at Louvain in the year 1645, also mentions Saint Ia, drawing largely from Saint Anslem, whom Dr. Cave (‘Historia Literaria’) considers [set quære] to be the author of the ‘Passio Sancti Guigneri sive Fingari, Pialæ et Sociorum.’ To condense these various accounts, the story of the first Christian mission to West Cornwall runs as follows:

‘Among the chief virgins of the Sacred Isle was Ia, called by some Iva, a follower of St. Barricius, who was a disciple of St. Patrick. She, leaving her native land, betook herself to Britain and was, indeed, one of that numerous company of 777 bishops, priests, virgins and other clerics who, renouncing worldly honours that they might inherit a heavenly crown, followed St. Fingar into Britain. St. Ia, being desirous to accompany these holy persons, but having no vessel to travel in, was praying on the shore, when she beheld a slender leaf conveyed by a great miracle to her feet. Embarking upon this frail craft she reached a British port called Heul, and joined herself to the band of missionaries.

‘Being by the shore, at a place where there was a great lack of water for drinking, St. Fingar, full of faith in Jesus Christ, and having prayed, fixed his staff in the earth, and immediately an inexhaustible fountain of purest water burst forth.

‘Next the saints came to a town called Conetronia. Here a certain woman, full of the fear of the Lord, showed them no little kindness. For, as her dwellings could not contain them all, and she had no straw for them to lie on, she took down the thatch from the roofs of her houses and with it made a bed for them. This most charitable woman gave them for food her only cow. When it had been killed, and its flesh eaten, Saint Fingar gave thanks and commanded that the skin should be spread over the bones of the cow. Then he invited his companions to pray, saying “Let us pray, brethren, that God, for the love of whom this woman most kindly provided us with this cow, may restore it to her.” And when he had ended his prayer, the cow appeared standing alive before them all, more beautiful than ever it was. Then the saint ordered that milk from this cow should be set before him; which having drunk, be besought God that the cow might thereafter afford thrice as much milk as other cows. This, it is related, was the case not only with that cow, but with all its progeny.

‘When morning was come, and the saints would continue their journey, they beheld the houses miraculously roofed anew. And when they had come to a certain wood, the rumour of their coming reached the ears of Theodoric, King of Cornwall, who had his castle at Revyer, on the eastern side of the estuary of Hayle; and he caused them all to be put to death by the sword on one and the same day.’

Such is a compendium of the somewhat vague and involved narratives of the authorities above named. Usher gives 460 as the year of the massacre. Whittaker surmises, with much reason, that Saint Ia is not taken to have been among the missionaries then martyred; and William of Worcester says that only ‘the greater part’ were put to death. Indeed, the latter historians, as Leland, distinctly record the tradition that Saint Ia arrived at Cornwall separately from the others:

‘The Paroch Chirch is of Ia, a noble Man’s Doughter of Ireland, and disciple of Barricus. Iä and Elwine with many other cam into Cornewaul and landid at Pendinas. This Pendinas is the Peninsula and stony Rok wher now the Town of S. Iës stondith. One Dinan, a Great Lord in Cornewaul, made a Chirch at Pendinas at the requist of Iä, as it is written yn S. Iës Legende. Ther is now at the very Point of Pendinas a Chapel of S. Nicolas.’

William of Worcester says:

‘Sancta Ia appulit in quoddam promontorio Pendinas appellato ubi in villa vel castello eiusdem nominis habitabat princeps potens nimine Dinan. Ille Sanctum Iam benigne recipuit, et, ea postulante, ecclesiam ædificavit, i qua, post predictum gloriosum matyrium, sacra reliquia huius virginis deponerentur. Et, a tempore ista, villa de Pendinas appellata est villa Sanctæ Iae.’

From these traditions as to the career of Saint Ia, it is evident that she spent some time evangelizing the Britons in the neighbourhood of the fortress of Pendinas (probably that of which the ‘Two Edges’ are the remains), secure in the protection of Dinan, the local chieftain, until, by the force or treachery of Theodoric, or Tudor, she was put to death in the same manner as her former companions.

In the Latin legend, as above condensed from Colgan, there are several points of peculiar antiquarian interest. It is probable that the mysterious 777, the alleged number of those forming the missionary expedition, is greatly exaggerated. What the real number was, it is impossible to guess. The ‘slender leaf,’ upon which Saint Ia sailed to Cornwall, was probably a coracle, the primitive vessel of the Celts, made of skins or canvas stretched upon a wicker framework; such boats may still be seen in remote corners of Wales and Ireland. ‘Conetronia’ seems to be recognisable as Conarton, a hamlet near the eastern shore of Saint Ives Bay2. The description of the charitable woman’s dwellings always named in the plural, with their conical coverings of rushes, forcibly reminds the reader of the clustered huts of Bosphrennis and the prehistoric ‘Picts’ house’ at Ayr. These and other similar ancient houses are formed of a cluster of small round ‘bee-hive huts,’ each of which was complete in itself, though but one component part of the whole habitation. A good illustration may also be seen in the hut foundations inside the Trencrom hill-fort.

‘Revyer,’ it will be observed, is the Norman-French translation of the Cornish word Hêl (Hayle), which, meaning ‘the River,’ has since been applied to a district or town. A farm-house in this locality still bears the name Reviere.

The Chapel of Saint Ia, which stood on the site of the present parish church, was erected either during her lifetime or soon after her martyrdom. Originally it was doubtless similar to the ancient oratories which still remain in the Saint Ives district, and which will hereafter be described. At her death the bones of Saint Ia were deposited in her oratory at the town of Pendinas, which soon after began to be called ‘Saint Ives’ in her honour, as above related in the words of William of Worcester. When the present church was built, early in the fifteenth century, the relics of the patron saint were translated to a beautiful shrine in the chancel; but at the Reformation this was destroyed, and Saint Ia’s remains scattered to the four winds. The Chapel of Saint Ia was, it appears, altered or added to long after its erection, for it is known to have possessed Norman architectural features. A plain octagonal capital, believed to have belonged to this chapel, was found some years ago near the church, and is now in the garden of a house on the Terrace.

Dr. Borlase says there was at Camborne a chapel dedicated to Saints Ya and Derwe.

Some writers give an alternative for to the name of our saint, calling her ‘Ia otherwise Iva.’ I have never been able to discover the authority for the latter variant. It does not occur in the MS. doubtfully attributed to Saint Anslem, nor does the letter v enter into any one of the numerous spellings used in the public records, until the thirteenth year of Elizabeth’s reign. The following is a chronological list of the various forms of the name of this parish, showing when the v first crept into the word. The documents referred to are subsidy rolls preserved at the Public Record Office:

- 1327. Parochia Sancte Ye.

- 1520. Parochia de Ya.

- 1523. Parochia de Seynt Ya.

- 1546. Seynt Iysse.

- 1547. Seynt Iyes.

- 1547. Seint Ies; Seynt Eyes.

- 1557. Seynt Iees.

- 1571. St. Yves.

- 1586. St. Iues.

- 1593. St. Ives.

The Cornish language always preserved the true name of the town. Carew, writing in the reign of Elizabeth, says:

‘This town is to this day called by the common people in the West, Porthia, St. Ia’s port.’

How, then, did this superfluous consonant intrude into the written and spoken name? Was it merely in an effort at greater euphony; or was it that, when the memory of the maiden patroness had faded away, her name became confounded with that of the Persian Bishop Ivo, who has given his name to the East Cornwall parish of Saint Ive, and to Saint Ives in Huntingdonshire? Later writers, indeed, have almost all professed themselves in doubt as to whether our town owes its name to the Irish Ia or the Persian Ivo; but the doubt seems to have been first raised by Alban Butler. At all events, as a matter of fact, our town has no associations either with Bishop Ivo, or with the popular Yves, the patron of the lawyers, whose name is borne by several parishes, and by thousands of men, in the sister county of Brittany.

It is true that, in the printed versions of William of Worcester’s ‘Itinerarium,’ we find the forms ‘Seynt Hyves’ and ‘Seynt Yves,’ side by side with the more ancient spellings (see ante, p.3), but it is open to question whether the ‘v’ is not introduced by an error of transcriber or printer, a century too soon.

1 [And also, now, in the dedication of St. Elwyn, Hayle. Ed.]

2 [And also an early name for the hundred of Penwith and a manor mentioned in Domesday. Ed.]

Webmaster

Webmaster