The following description is lifted directly from [Quiller-Couch 1898] from an article written by Thurston C. Peter entitled “Notes on St. Levan”. It must be read in the context of that date. The contemporary photographs are by J. C. Burrow, of Camborne and were printed with the original article.

CHURCH OF ST. LEVAN

As will already have been learnt from the essay on St. Buryan, this church was formerly a parochial chapelry only, dependent on the Collegiate Church at that place, and the parish was only converted into a rectory, in the patronage of the Duke of Cornwall, in 1864. The church was restored in 1874 by Mr. John D. Sedding, who (as every architect should do) left on record some notes of the state of the church previous to restoration.

The church is built into — we had almost said has grown out of — the side of a hill, in a lonely and secluded valley, and until recently there has been no rectory house.

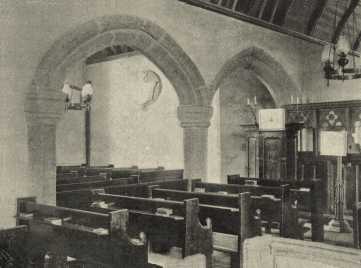

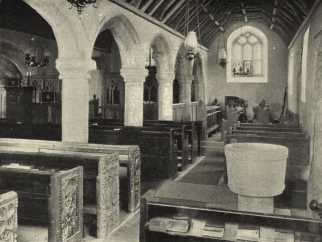

The church consists of a disengaged western tower of two stages, the lower stage being 16 feet 4 inches square and the upper slightly less; nave, chancel, south aisle and north transept. The transept is connected with the nave by two arches, carried on octagonal granite pillars with capitals of three different designs. These capitals appear to be of earlier date than those of the south arcade, though of later than the transept itself, which is of the thirteenth century. It looks as if an aisle had at one time been contemplated on the north, and subsequently abandoned. The whole arrangement should he compared with that on the south side of Zennor, Germoe, and St. Mawgan-in-Kerrier. The arrangement of the walls at the angle of transept and chancel inclines us to think that there was at one time a hagioscope here. Previous to the usual cutting-down by churchwardens, the roof was of high pitch, and was left untouched in that respect when the new roof of the nave and that of the south aisle were constructed in the fifteenth century.1 The decorations of the walls of the transept (revealed when the plaster was scraped off during the restoration) were also apparently of thirteenth-century date, or perhaps early fourteenth, as is also a portion of the chancel wall. The font of porcelain stone, with circular bowl (18½ inches inside diameter), bearing a 3-inch band of shallow tooth ornament round the top, and a bold cab1e-mou1ding round the bottom, with four sunk cusped circles enclosing geometrical designs in low relief on its sides, is probably of the same age, though the cusping of these circles may indicate a somewhat later date. The perfectly preserved and very beautiful square stoup, with panelling of three pointed arches on its front, we unhesitatingly regard as of the thirteenth century. With these exceptions (and perhaps we may include the tower) the whole church is of Late Perpendicular of the fifteenth century; but the tracery of the windows is quite modern, the architect having had to substitute stone mullions and tracery for the window frames of wood which had been placed throughout the church by the church-wardens of the eighteenth century. The restoration of these windows (as indeed of the whole church) has been carried out with great taste. We cannot, however, but regret that the lancet light in the west wall of the transept has been so restored as to lose the interesting feature that marked it when each side of its arch was formed of a single stone — a local peculiarity of rare occurrence in such early work. Perhaps, however, the old window was ruined beyond repair, but the restoration should have followed the original lines. Certainly the whole church, when restored in 1874, was in such a condition that it was proposed to build a new one in its stead in another part of the parish. This fortunately was prevented.

THE STOUP

The tower is probably older than the main part of the church. It is of admirable proportions, and, especially when seen from the west, is a most effective structure, its windows, with tracery of Catacleuse stone, being of very good design. The western doorway, with its arch of a single cavetto moulding with chamfered edges, skilfully stopped at the base, is specially worthy of notice. It contains three bells:—

Tenor C, 5 Cwt. (approximately), inscribed ‘1641’ in broad flat figures. Diameter at the mouth 33¼ inches.

II D, 4c. lq. 7l. 1881 (cast by Messrs. Mears & Stainbank). This bell replaces one of 1754, bearing the trade mark of Abraham Rudhall (whose business Messrs. Mears & Stainbank now carry on) and the names of the then churchwardens.2

Treble E, 4 Cwt. (approximately). Inscribed ‘Thomas. Iohn: C W 1696.’ Letters much corroded. Bell cracked. Diameter at the mouth, 28½ inches.

NORTH TRANSEPT

The tower is separated from the nave by a round-headed arch springing from pentagonal imposts, and its floor is two steps above that of the nave. The staircase is newel, in the thickness of the wall, at the north-west angle.

Entering the church by the south porch, notice the stone seats on each side and the stoup already referred to; also the fact that the floor of the church is by two steps lower than that of the porch.

Within the church the most interesting objects (besides those already mentioned, to say nothing of the general effect, which, by some mystic touch of art, conveys no sense of smallness) are the rood-stairs in the south wall of the aisle; the arcade of six low four-centred arches supported on monolith octagonal granite pillars, only 6 feet 8 inches apart; the carved bench-ends (some of which are shown in the illustration), and the chancel-screen, which is partly new and partly made up from the beautiful remains of the fifteenth-century rood-screen. On one bench-end may be seen a monk with breviary and ‘discipline,’ on another a woman with her hair neatly gathered in a net, such as was worn about the middle of the fourteenth century, and on the top of her head a cap in evident imitation of the style of a man’s helm as shown on the adjoining panel; while the ends of two other benches have spirited representations of two jesters: these were formerly placed near the door, but are now doubtless merely restored to their original use. It has been suggested that the jesters so often represented in church are symbolic of the scoffer at the sacred mysteries; but probably they are merely the squire’s jesters. The local craftsmen of those days knew nothing and cared less for the conscious scruples that define one thing as suitable in dramatic art, another as suited for the church. The two were identical, except that they put their best work into the church. In many churches the element of comedy is boldly introduced, for the time had not then come when laughter was regarded as a sin, and those who would be thought religious must assume an unnatural gravity and lay their humanity aside. One other bench-end is interesting, having on it the initials ‘AV.’ Of this Blight gives an illustration, but omits a heart; cut in the lower loop of the V, which, as St. Levan was a chapelry of the Augustinian Canons of St. Buryan, and a heart was the emblem of St. Augustine, is of interest, even if its presence here is a mere coincidence, as it probably is. The bench-ends seem to be of the first half of the fifteenth century. We regret that the benches are, for the most part, quite unworthy of the ends; anything more ugly than the dark green paint which has been applied to them it is impossible to imagine. The Communion-table is of wood, with a vulgar-looking attempt at superaltar and reredos. In the south wall of the chancel is a modern piscina with credence shelf above it; and in the north wall is an ogee-headed niche (removed from the south side and placed where it is for preservation), which until recently bore slight traces of colouring, thirteen inches across and containing two shallow basin-like depressions without drains. In spite, however, of no drains being now traceable, we have no doubt this is a piscina of the fourteenth century, when two basins were not uncommon. The hexagonal wooden pulpit bears the date 1752, amid is in better taste than was then usual.

The church plate consists of a paten and chalice, both of silver, presented to the church in 1887, and an undated chalice of impure metal, 6½ inches in height and with a flat cover, which was formerly used as a paten. It is of good shape, with a neat scroll pattern encircling the bowl. It bears the initials T.G.C + O + S.J

In the Parish Registers the first entry of Baptism is April 7, 1700; of Marriage, September 9, 1701; and of Burial, July 1, 1700.

SOUTH AISLE

In the churchyard are two remarkable crosses (1) a beautifully proportioned wheel cross by the south porch, nearly 7 feet high, having on the front a rude figure of Christ wearing a tunic with sleeves and very full at the bottom; there is an incised pattern on the lower part of the shaft; on both sides, also, are incised patterns, and on the back a very exquisite cross in relief, the head being like (2) that at the north-east entrance by the side of the lich-gate (see illustration). These crosses are apparently both of comparatively late date. On the north side of the gate is a stone with a figure in a tunic, the head and parts of the arms having been broken off. The ancient lich-stone is coffin-shaped, and On each side of the entrance are stone benches. One of the stones on the south side bears the initials of the churchwardens and the date 1794. At the south-west entrance is another roofless lich-gate with stone seats and oblong lich-stone. To the south-east of the church is a curious granite boulder, split part way through, as to which the natives hold that when the two pieces go entirely apart the end of the world is at hand, in accordance with St. Levan’s prophecy:—

When with panniers astride,

A pack-horse one can ride

Through St. Levan’s stone,

The world will be done.

Anxiously do the parishioners scan this stone each Sunday morning as they enter the church. It was on this stone, legend tells us, the Saint used to rest after the fatigue of fishing, and on the same authority we learn that the split in it was made by him with a blow of the fist, and with a view to leaving behind him some abiding memorial of himself. The stone must clearly have been venerated, or the builders of the church would never have neglected such handy material.

In the field adjoining the churchyard on the east is another cross of ruder execution than the other two, but of interest. It is similar on both faces, the crosses cut on each side having an inclination to the right, doubtless in reference to the direction in which Christ’s head is traditionally said to have inclined at the Crucifixion.

As in the case of St. Buryan and many other Cornish Saints, little is known of St. Levan, who gives his name to this parish, as well as to the estate of Selena in it, and possibly also to Porthleven. Carew (Survey of Cornwall) calls him St. Siluan, and in the ‘Inquisicio Nonarum’ of 1340 ‘Capella Sancti Siluani’ is mentioned under Burian. Mr. Lach-Szyrma, in his ‘Church History of Cornwall,’ suggests that the stone at St. Just (in Penwith), which is generally read ‘Silus hic jacet,’ refers to this Saint, and, in confirmation of his suggestion, prints the name with a big gap ‘Sil . . . s,’ which certainly does not exist on the stone itself. The name of the parish is pronounced locally ‘Sleven,’ and in the valuation of the lands, &c., of Penwith, quoted in a note to the essay ‘St. Buryan,’ it is called Selevan. Such is all that can be said to be known about St. Levan; whether he was Irish or Armorican is not clear — in history he is a name and nothing more, but in legend his place is larger than that of most. Walking along the path that leads from the church past Bodellen (where the hut of our Saint once was), and by Rospletha to St. Levan’s rocks, whither the Saint was in the habit of going to exercise his skill as a fisherman, you will observe that the grass where his holy feet once trod is greener and sweeter than any around. One Sunday morning the holy man was walking along this path when one Johanna, who was herself engaged at the time picking herbs in her garden at Rospletha (still called Johanna’s garden), sternly rebuked the Saint for fishing on the Sunday (by the way, there is quite a modern ring about this, human nature has not varied much in some 1,300 years). They came to high words (our Saints were always powerful in that line), and St. Levan called Johanna a foolish woman, and prophesied that if any other child was christened by that name in his well she should be even more foolish. Wherefore it is that those who desire to call their children by the name of Johanna wend their way to the neighbouring church of St. Sennen.

N. E. LICH-GATE AND CROSS

Formerly some designs amongst the carving in the church recorded an event in St. Levan’s life. Here and there two fishes might be seen on one hook. Seated one day on his favourite rocks he had thrown his hook into the sea, and on drawing it found two chads caught by it. He did not want two fishes, and anxious not to be unfair to either, he threw both back into the water. Three times this happened, and the third time St. Levan concluded that Providence willed he should take both fish home, and he accordingly did so. On reaching his hut he found his sister St. Breaca (some say St. Manacca) awaiting him with two children, whether her own or some one else’s does not appear. The fish were cooked, the children ate eagerly, and, neglecting the bones, were both choked. That this legend (which has variants, the best being that which relates the capture and rejection of a single chad which the Saint rejected as not dainty enough) is true is clearly proved by the fact that the chad is still known as the ‘Chuck chiel.’ The legend of St. Levan’s stone in the churchyard we have already referred to.

A little distance from the church, on Porthchapel Point, are the ruins of St. Levan’s well, and here formerly is said to have been his hermitage. At Porthcurnow, about a mile from the church, are the ruins of an ancient chapel, one of those interesting little buildings formed of two squares, as at Perran and Madron It is impossible to say what is the date of these structures, but they were no doubt erected long before the coming of the Normans, and their rectangular form and unbroken sides have had a clearly traceable effect on the traditions of the Cornish church-builders. Like the chapel on Chapel Carn Brea, it was erected in a spot already sacred as a place of burial.

1 Of course, the ends of the roof timbers rotted away through damp and neglect, and the rude remedy adopted was to cut them shorter and refix them. The original pitch of the roof of the nave is evidenced by the tower, where the dripstone that was carried over the old roof is now more than a foot above it, and also by the relative positions of the roof of transept and nave before the former was restored. There is a good illustration of the transept before its roof was lowered in Blight’s Churches of West Cornwall [Blight 1885]. Blight’s illustrations of the capitals of the piers of the transept arches are incorrect.

2 The churchwardens of the eighteenth century and early nineteenth century, who did more to destroy the beauty and history of our churches than the much abused Puritans of one hundred years earlier, seem everywhere to have been proud of their work. At St. Buryan they recorded their names and the date of their mischief on the tower steps at Wendron their initials are conspicuous on a pinnacle of the tower; and here at St. Levan their names may be seen also on a stone of the lich-gate their favourite place of record was the sun-dial. Here, however, the sun-dial escapes, and bears merely the legend ‘Sicut umbra transeunt dies.’ Had these worthies known what would be the feeling of the present generation towards them, they would, for very shame, have erased their names even from the parish registers.