We must now give a full description of this church, as it at present exists, noting, when necessary, the points wherein its present condition differs from its state in the past.

Saint Ives Church stands on the very edge of the shore of Saint Ives harbour, in a situation unusually low for a parish church. Even its tower can be overlooked from several points on the higher land close by. This tower is remarkably high for Cornwall, and is one of the finest in the county, though its effect would be more striking if its buttresses were not so slender. It is 119 feet high, of four stages, buttressed on square; has a battlemented parapet, and battlemented pinnacles resting on angels. The belfry windows, larger than usual, are each of three lights and transomed.

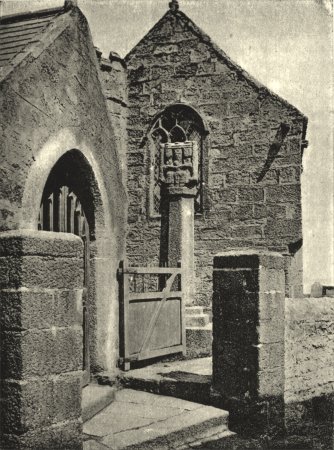

ST. IVES CHURCH, SOUTH PORCH, SHOWING THE ‘ORGAN-TOWER.’

The church is a large one, eighty feet long and sixty feet wide, and consists of chancel, nave with western tower, north aisle and south aisle, all perpendicular in style. At the eastern end of the south aisle is a chapel, wider than the aisle, added rather later; it is known as the ‘Trenwith aisle,’ from its having been erected by a member of that ancient family. With the exception of this chapel, the entire structure seems to have been built at the same period; nor are there any remains of the earlier structure. The church could formerly boast of a beautiful oak rood-screen, and an organ, which was very large for one constructed in the fifteenth century. Both organ and screen were removed and destroyed by the Puritans in 1648. Hicks says that this organ cost £30, and that it was one of the first organs erected in Cornwall. He saw the pipes, and says they were of large size. Some of them did duty as drain-pipes and water-spouts in the town, even later than the time of Hicks.

The organ stood in the rood-loft, the staircase leading to which remains at the north-west angle of the Trenwith aisle. Outside the church this staircase is indicated by a small piece of battlemented wall, situated between the west end of the Trenwith aisle and the south porch. This rood-staircase is popularly called the ‘organ-tower’—a term which significantly points to the time when the organ stood in the rood-loft.

Each aisle has seven bays, with piers consisting of four shafts with intervening ogee mouldings; the arch mouldings correspond. The roofs are of the waggon form usual in Cornwall, but very handsome and perfect, elaborately carved, and with full-length oaken figures of angels at the springings of the braces. These figures are continued all the way down the nave; they are each about a foot long, their wings folded in front. Each head is surmounted by a cross, symbolical of the angels, and the figures all hold different objects, as a triple shield, an open book, a wreath. In the chancel-roof the braces and purlins are intersected diagonally by a raised and continuous moulding, giving a pretty net-like appearance. The suggestive vine-pattern is carried along the wall-plate both in chancel and nave. Richly carved bosses are placed at the intersections of the diagonal lines, and of the purlins and braces. The bosses in the roof of the Trenwith aisle are carved with double eagles.

In the east wall of the north aisle, and adjoining the chancel, is an arched recess, with jambs resting on the floor, four feet two inches high, and two feet four inches wide. Possibly this marks the situation of the shrine of Saint Ia, whose body was preserved in the older chapel, and was translated to the present church on its completion. William of Worcester, writing in the year 1478, says:1

‘Sancta Hya, id est Seynt Hy ...... virgo iacet in eccliã paroch ville Seynt Hy ...... et eius dies agitur iiio die ffebri.’

(Saint Hya, that is Saint Hy, virgin, lies in the parish church of the town of Saint Hy, and her day is kept on the 3rd of February.)

More probably, however, the said recess is an ‘Easter Sepulchre,’ or reposoir, in which the consecrated host was enshrined, amid lights and flowers, from the high Mass of Maunday Thursday until that of Holy Saturday.

The capitals of the nave pillars are delicately moulded, with a slight carving of foliage around the centre. Along the string-course runs a strip of oak similarly carved with vine-leaves and grapes.

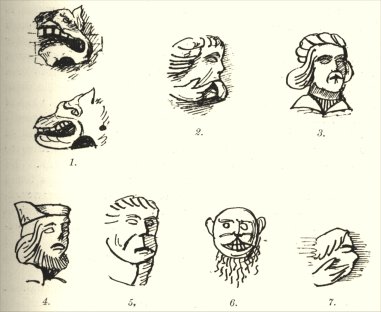

FIG. 1.—GARGOYLE ON THE WEST WALL OF THE TRENWITH AISLE, ST. IVES CHURCH. FIGS. 2–7.—GROTESQUES ON SOUTH WALL OF ST. IVES CHURCH.

Several well-sculptured corbel-heads under the roof of the south chapel or Trenwith aisle appear, says Blight, to be of earlier date than the wall into which they are built. These are seven in number:

- A dragon’s head (gargoyle).

- A man’s head, with hands pulling open the mouth, putting out the tongue.

- A man’s head, with long hair; part of jacket and vest showing.

- A man’s head, bearded on the chin, having long hair, and a cap with a lappet at the back turned up.

- A man’s head, face clean-shaved, deep collar.

- Apparently an ape’s head; bald, grinning, and showing teeth, long thin beard on chin.

- Same as No. 2, but not so well preserved.

No. 1 is on the west wall of the Trenwith aisle, near the south porch. Nos. 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6 are ranged in this order from west to east, under the roof of the aisle. No. 7 is at the north-eastern corner.

The raison d’être of the grotesque in church architecture has long been a puzzle to antiquaries, and various have been the guesses hazarded as to the motive which led the old church-builders to introduce such monstrosities. A common notion is that the regular and secular clergy satirized each other through the medium of these stony imps. There could not be a greater mistake; no such permanent libelling would have been permitted at any period of the Church’s history. A better acquaintance with the spirit of the old artists will show the student that these ecclesiastical satires are directed against the follies and vices of mankind in general. The occurrence amongst them of priestly and monastic types is to be ascribed to the artist’s idea of symbolizing the vice of hypocrisy in that manner, according to the old proverb, ‘The cowl does not make the monk.’ No doubt also the fact of the grotesques being almost always found outside the walls indicates a desire to contrast the ‘outer darkness’ of the unregenerate world with the beauty and sanctity of the Church’s interior. The mocking, leering grotesque, moreover, aptly symbolized the unbeliever scoffing at the sacred mysteries enshrined within, and the demons of the deadly sins put to flight by the Gospel and the sacraments.

On the south wall of the Trenwith aisle is a wooden sun-dial. Two or three years ago the inscription on it was still partially legible, as follows:

‘TRANSI [UNT OMNES MORIB?] UNDI.

SIC TRANSIT GLORIA MUNDI.

AND: CURNOW

TOWEDNACK. 1739.’

The dial-board was repainted in 1885, when the old ‘healing-stones’ of the church roof were replaced by slates, and the inscription has vanished. It ought to be restored.

A thorough overhauling of the south porch might possibly bring to light the holy-water stoup, to the right of the inner doorway, and the niche for a saint’s image over the outer doorway, as at Lelant.

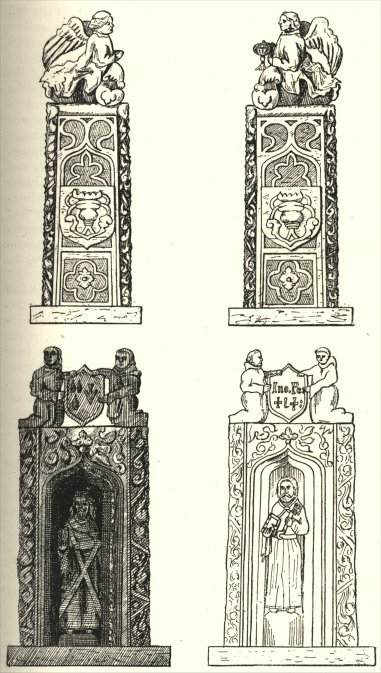

BENCH-END CARVINGS IN ST. IVES CHURCH.

In 1883 the writer observed a square block of granite, about four feet long by one foot broad, and half a foot thick, which lay across the gutter, at the church end of the Warren. On one of the wide faces of the block were rough carvings—viz., at one end a saltire or Saint Andrew’s cross within a square, and below two keys of ancient shape ranged side by side, the three carvings being equidistant from each other. This stone was evidently taken from the church, as is evidenced by the symbols of the two saints. In the following year the block was built into a neighbouring wall, and whitewashed over.

The font, three feet ten inches high, is of granite, and apparently a copy of a font of the thirteenth century. At any rate, it is almost certainly contemporaneous with the church. Around the bowl are four angels, each holding a shield, and connected by a band bearing these words in raised Early English characters: ‘Omnes baptizate gentes’ (Baptize all nations). The bowl is supported by a circular pedestal, flanked by four smaller columns; on its circular base are four sprawling dragons, representing demons cast out by the sacrament of baptism. There is a very similar font at Illogan, which was, perhaps, the model of the Saint Ives font.

A striking feature of the interior of this church are the fine carved oak benches, black with age. Tradition attributes this artistic work to Ralph Clies, the master smith, who also contributed the now missing screen. The following is a list of the subjects represented on the bench-ends, some of which have been removed from their original positions.

On the front panels of two large seats now in the chancel, laving been removed from the west end of the church, are shields bearing:

- Hammer, pincers, nails and horseshoe.

- Hammer and anvil.

- Man’s head and shoulders, with cocked hat and frilled collar; face shaven.

- Facing to the last a woman’s head and shoulders, with tight-fitting cap. These two heads are supposed to be portraits of Ralph Clies and his wife; but they probably represent a jester and a scold (for the faces seem to have been purposely made ugly), or a Roman soldier, and the smith’s wife of the Cornish legend of the Passion, who furnished nails for the crucifixion. Similar carvings exist at Saint Levan.

- Pair of bellows.

- Ladle, hammers and clefts.

It will be seen that all these are a smith’s implements, but all were probably intended to bear some reference to the crucifixion.

BENCH-END CARVINGS IN ST. IVES CHURCH.

The standards, which are now fixed at the east ends of the same two seats, occupy very nearly their original position, as they are undoubtedly a portion of the ancient chancel-stalls. They are carved with the figures of Saints Peter and Andrew; the former holds a key and a closed book, and on the top of the bench-end over his effigy are two Benedictine monks supporting a shield, on which is the inscription, ‘John Peyn.’ The standard with the figure of Saint Andrew is surmounted by two similar monks, with a shield bearing two coats of arms impaled:

- Three pine-apples.

- An arrow-head in pale reversed.

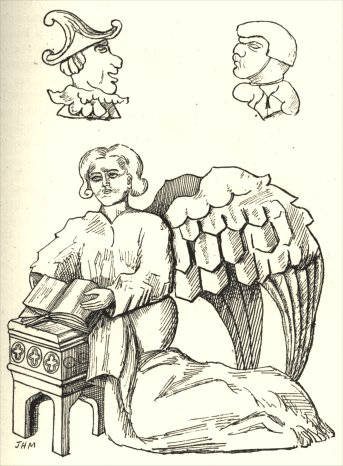

These are the arms of John Peyn, and the three charges in the dexter half are supposed to represent pines, though they are more like pears; but the probable explanation is that the carver had never seen pineapples. Another old bench-end in the Trenwith aisle is a beautiful example of wood-carving. It is surmounted by an angel holding an open book, and kneeling at a reading-desk; and this too, beyond all doubt, originally belonged to the chancel stalls, as well as two other bench-ends, ornamented with late perpendicular carving, each surmounted by a kneeling angel, of whom one holds a pyx, or vessel to contain the conseccrated wafers. In the chancel is an oaken sedile of apparently the same period as the bench-ends; the side-panels are perpendicular in character, and are carved with the monogram J. S. There is also another wooden seat of a later period, and a small portion of the rood-screen is still preserved. Other bench-ends in the aisle bear various symbolical devices, such as a head with three faces, emblematical of the Trinity.

In the first half of the present century there must have been many more ancient benches in Saint Ives church than now remain there, for it is said that a former churchwarden and parish clerk had picture-frames made out of old oak from the benches. The present pulpit is also made of panels from them. Some years ago this fine oak work was covered with a coat of white paint by order of a churchwarden, but was speedily cleansed with turpentine by the vicar.

In 1838 the pulpit was moved from the side to the middle of the chancel. The sounding-board was then turned into a cover for the font, over which it was supported on four slender pillars (Courtney’s ‘Guide to Penzance,’ 1845).

OAKEN SEDILE IN ST. IVES CHURCH.

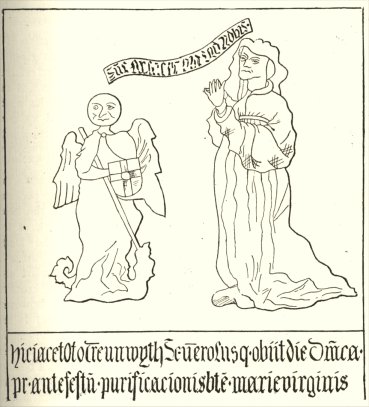

The only pre-Reformation sepulchral monument in this church a brass, the original site of which was the floor of the Trenwith aisle. At the restoration of the building, the brass and its slate matrix were fixed on to the east wall of the aisle. This brass commemorates Otho de Trenwith and his lady, and bears an effigy of the latter kneeling before Saint Michael. The features of the kneeling figure represent an elderly woman, clad in an ample gown and hood bound round the waist by a girdle; the hands are joined in the attitude of prayer. The archangel, his wings extended, is trampling on the dragon, which he transfixes rough the mouth with his lance; while with one hand he holds a small shield, which bears a cross voided at the centre. Above the figures is a scroll, inscribed: ‘Sancte archangele ora pro nobis’ (Holy archangel, pray for us). ‘Some perplexity may be felt at the appearance of Saint Michael’s head here, which looks like nothing so much as a Dutch cheese. The fact is, that when this brass lay on the floor, the feet of passers-by had gradually erased the features of the archangel, leaving only the circular nimbus or glory round his head. Some well-meaning but misguided restorer of later days has evidently taken the nimbus to be the outline of the head, and has roughly filled in eyes, nose and mouth to correspond!

THE TRENWITH BRASS.

Beneath the figures is the following legend:

‘Hic iacent Oto Treunwyth Generosus qui obijt die dominica proxima ante festum purificacionis beate marie virginis Anno regni Regis Edwardi iiijti secundo qui fuit vir benignus deo et mundo ac bene dispositus Et domina Agnes Consors eius. Quorum animabus propicietur deus.’

(Here lie Oto Treunwyth gentleman, who died on the Sunday next before the festival of the Purification of the Blessed Virgin Mary, in the second year of the reign of King Edward the Fourth; who was a man benign and well disposed to God and the world—And the Lady Agnes his wife; upon whose souls may God have mercy.)

The original is, as usual, much contracted, and a portion of it is somewhat doubtful; but the above is the reading as given in Dunkin’s work on the brasses of Cornwall. The year referred to was 1462–3, and it would seem that Otho Treunwyth was the founder of this his family chapel. In the middle of its south wall, on the outside, is a small doorway, long blocked up, consisting of an obtuse perpendicular arch, in a square setting with quatrefoils carved at the upper corners. Of course, this was the Trenwiths’ private entrance to their chapel.

Between the Trenwith aisle and the south porch stands a tall granite cross, square-headed, on an octagonal oblong pedestal fixed into a platform of three steps. On the side of the head which faces westward is carved an arcus fœderis (‘ark of the covenant’), the mediæval term for an effigies of the Deity exhibiting to the world His crucified Son. God the Father is represented as an aged man of venerable aspect, bearded and wearing a crown, seated and upholding the arms of the crucifix. In the top corners are two shields, no bearings being, however, distinguishable. On the eastern side of the cross-head is the Madonna, crowned and holding the Infant Jesus, with the effigies of two persons standing on either side of the central figures. On the narrow south side of the cross-head is carved a bishop, in mitre and chasuble, holding a pastoral staff in his left, and blessing with his right hand (Saint Uny?). On the north side is a female figure, robed and crowned, no doubt representing Saint Ia. The cross-head is battlemented at the top. This cross, a beautiful example of early fifteenth-century work, was thrown down by the Reformers, and remained half buried in the soil of the churchyard until it was replaced, about the year 1850, at the cost of Robert Hichens, Esq., of Saint Ives and London, a gentleman to whose munificence and taste the parish church of Saint Ives is greatly indebted.

Webmaster

Webmaster